Primary ciliary dyskinesia, also called Kartagener syndrome, can be an overlooked underlying cause of bronchiectasis, according to recent research from Tehran University of Medical Sciences in Iran, describing six patients with the condition. The study suggests that clinicians should consider the diagnosis even when patients lack some of the typical features, to offer early diagnosis and treatment.

Primary ciliary dyskinesia is a genetic condition inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion, meaning that two mutated copies of a gene, one from each parent, need to be present for the disease to develop.

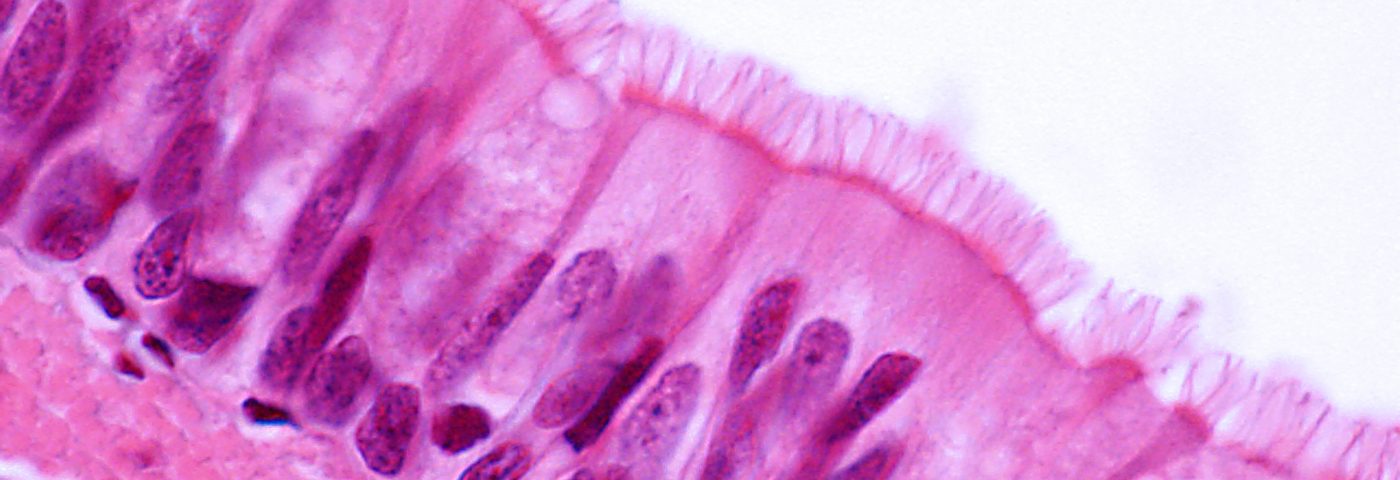

The cilia lining the airways — like a mat of short fur that is capable of movement — helps the airways to get rid of excessive mucus and other substances. In this hereditary condition, however, the cilia don’t move, giving rise to repeated airway infections.

Some of these patients also suffer another, very characteristic feature — an inversion of the position of the heart and other organs from the left to the right side of the body, termed situs inversus. If this trait is not present, along with a number of less specific characteristics, such as ear infections and male infertility, primary ciliary dyskinesia can be hard to diagnose, and is often not established until other causes of bronchiectasis have been ruled out.

A positive diagnosis also needs to make use of electron microscopy, which is an expensive method only available in specialist centers. The combined effect of these factors is that physicians often fail to include primary ciliary dyskinesia when trying to establish a cause of bronchiectasis.

In a case series, the report “Primary ciliary dyskinesia in six patients with bronchiectasis“ describes patients who suffered bronchiectasis from childhood, but were not diagnosed with primary ciliary dyskinesia until they participated in an earlier examination of 40 bronchiectasis patients by the research team.

In the study, published in the journal Pneumologia i Alergologia Polska, the patients were ages 9 to 25, and four of them had symptoms starting at birth. In two other patients, symptoms were discovered when they were 1 and 4 years old. With the exception of one patient, diagnosed after only two months, the other five patients had to wait between five and 16 years to receive a diagnosis.

All the patients had parents that were close relatives — an unsurprising finding, given that the rate of marriage between relatives in Iran is as high as 38.6 percent — and some reported that other family members were affected by similar conditions.

Patients also shared the disease characteristics of repeated upper airway infections with chronic cough, difficulty to breath, sputum production, wheezing, inflamed sinuses, and pus-containing mucus discharge from the nose and sinuses. Four patients had recurrent ear inflammations, but only one patient had reversed organs. A few patients developed continual decrease in lung function and obstructive lung disease.

High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the chest showed three patients with obvious signs of bronchiectasis and another with early signs of the condition. The remaining two patients had obstructed airways, including a total loss of sinus cavities.

The research team concluded in their article,”PCD [primary ciliary dyskinesia] should be considered as a probable underlying disorder in patients with bronchiectasis. Past medical history of otitis media and history of similar clinical findings in family members should raise suspicion toward PCD.”