Oklahoma suffers more tornadoes than any other state, has the highest per-capita rate of women in U.S. prisons, ranks second in the number of teen births per 100,000 teenage girls, and has the nation’s third-highest rate of uninsured residents — with 13.9% of all Oklahomans lacking health coverage.

As if that’s not enough, the Sooner State has a new dubious claim to fame: it’s the worst place in the United States to live for anyone with a rare disease.

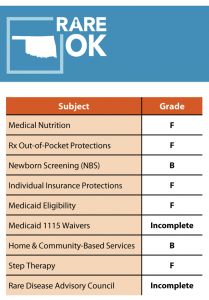

That’s according to the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD), which every year since 2015 has graded all 50 states from A to F for their performance on issues affecting the roughly 30 million Americans who have rare illnesses.

That’s according to the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD), which every year since 2015 has graded all 50 states from A to F for their performance on issues affecting the roughly 30 million Americans who have rare illnesses.

In the 2019 report, Oklahoma received a whopping five F’s— more than any other state — one each for medical nutrition, protection for out-of-pocket prescriptions, individual insurance protections, Medicaid eligibility, and step therapy. The Midwestern state got B’s in two other categories, newborn screening and home and community-based services, and not a single A.

“Oklahoma needs help. I’ve looked at everybody’s report card, and we’re the worst,” said Jade Day, the Oklahoma volunteer state ambassador for NORD’s Rare Action Network.

A resident of Muskogee, 48 miles southeast of Tulsa, Day is also vice president of the nonprofit group A Twist of Fate-ATS, which seeks a cure for arterial tortuosity syndrome.

“We just can’t keep doctors. The Children’s Hospital at St. Francis [in Tulsa] just dissolved their pediatric cardiovascular surgery program,” she told BioNews Services — publisher of this website — during the NORD Family & Patient Forum in Houston in late June. “We have plenty of general doctors but we lack specialists. They just don’t stick around.”

Opioids and poverty

Oklahoma, home to just under 4 million people, is also ground zero for the nation’s opioid crisis.

Earlier this year, the state and Purdue Pharma— the Connecticut-based maker of the prescription painkiller OxyContin — agreed to a $270 million out-of-court settlement in what the Washington Post called “the first major test of who will pay for more than two decades of death and addiction sparked by prescription opioids.”

Under terms of the deal, according to the article, Purdue will contribute $102.5 million toward a new foundation for addiction treatment and research at Oklahoma State University. The Sackler family, which owns the company, will pay an additional $75 million in personal funds over five years.

Additional terms include prohibitions through 2026 against Purdue promoting opioids in Oklahoma, or visiting doctors to persuade them to buy its products.

The opioid crisis, Day said, is emblematic of Oklahoma’s deeper problems when it comes to healthcare. Much of that, she said, is tied to poverty.

“We do have a huge crisis in Oklahoma. In my small town, we have opioid deaths every week. I have a friend who lost his mother over an opioid overdose,” she said. “I think our state is losing focus.”

Keeping doctors in Oklahoma

Earlier this year, Day and her friends petitioned the Oklahoma Supreme Court for expanded Medicaid access after the state’s legislature refused to consider a bill to do just that. At the moment, she and her fellow Oklahoma state ambassador, Tamra Misak, are scrambling to collect the necessary 178,000 signatures.

“No matter how much money Oklahoma gets, poverty is still a huge problem,” said Day, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation. “My city is so impoverished, every child in the district gets free breakfast and lunch — even the doctor’s kids. We’re at a level of poverty where they cover everybody, and rural poverty is even worse.”

She added: “Drive 30 minutes out of Tulsa and you hit towns that are dying. My town had a mall and we’ve lost every store in it.”

Part of the problem is Oklahoma’s huge dependence on the oil and gas industry. When petroleum prices drop, Day said, “my friends’ hours get cut, or they’re laid off for two weeks at a time.”

Then, there’s “an Indian population that suffers from generational PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder], alcoholism and heavy crystal meth use. And if your state is impoverished, you’re not going to recruit the doctors and professionals you need to treat rare-disease patients, most of whom are on Medicare.”

Day’s 11-year-old son, Gavin, has FG syndrome, an X-linked neurodevelopmental disorder that causes learning difficulties, weak muscle tone, cardiac defects, and vision problems. Her two other boys, 8-year-old Isaac and 5-year-old Andrew, are healthy.

“A lot of friends here at NORD ask me, ‘Jade, why don’t you just move to another state?’ I tell them I can’t, Oklahoma is my home,” she said. “I live inside my Cherokee Nation, and it’s hard to leave that comfort zone.”

Looking for the positive

Kristen Angell, NORD’s associate director of advocacy, oversees the Rare Action Network.

“Depending on the areas they’re in need of improving, it could be a matter of educating the elected officials who can influence policy changes at the state level on behalf of the rare disease community,” she told BioNews when asked why Oklahoma did so poorly in this year’s ranking.

NORD currently has Rare Action Network members in all 50 states plus the District of Columbia, and ambassadors in 32 states. She noted that California (the nation’s most populous state, with nearly 40 million residents) consistently scores the highest when it comes to parameters for rare-disease patients.

In the 2019 ranking, California — which NORD called “close to being a model state when it comes to enacting policies” affecting rare disease patients — received six A’s, one B and one C. Other states that ranked well are Minnesota and New York, each with four A’s. At the other extreme were Arkansas, Hawaii, Kansas, Kentucky and Mississippi, each with 3 F’s.

“A lot of these issues are state-specific, so the leaders we want to influence are at the state level,” Angell said. “At the national level, we meet on different topics, making sure there’s equitable access and treatment available — for example, newborn screening is both a federal and state issue we focus on.”

The idea of the State Policy Report Card, now in its fourth year, isn’t to shame anybody, but to effect change in state capitals.

“In every report, there is a positive. We want to acknowledge that,” Angell said. “When we walk into a lawmaker’s office, we don’t say, ‘hey, you guys need to clean this up.’ If we’re not actively working in a state, rare diseases may not be a focus point for anybody. A lot of times, they don’t even know this report card exists. Once they see it, their first words are usually, ‘what can we do to help?’”